When Art Becomes an Asset Class

Thoughts on the rising interest in art investment funds.

Artnet’s Art Market Minute podcast caught my attention this week with a sixty-second discussion titled “Are art investment funds evolving?”—a question that feels particularly relevant as global markets, including Canada’s, continue to navigate economic uncertainty. While art investment funds have gained traction in the U.S. and Europe, Canada’s art market operates within a different financial and regulatory landscape, making such funds less common. Yet, Canadian investors are not entirely shut out of this attention-getting sector. Whether through international art funds, private acquisitions, or alternative investment models, the intersection of art and finance is becoming increasingly relevant.

But what exactly is an art investment fund? How have they evolved? And, more broadly, what happens when art—one of the most extraordinary forms of human expression and containers of history—is treated purely as an asset class, akin to stocks, bonds, or even cryptocurrencies?

Art investment funds are private investment vehicles designed to generate returns through acquiring and selling artworks. They are managed by professional art investment firms, which charge management fees and take a portion of the profits. While all art funds employ a "buy and hold" strategy, they differ in size, duration, and investment focus.

The art market’s lack of regulation, opaque pricing, and illiquid nature (art typically does not sell fast and unlike a stock requires physical storage and maintenance) creates both opportunities and risks. Opportunities include arbitrage advantages, when an asset is bought in one market and sold in another for a higher price (think from yard sale to Sotheby’s or from Canadian to Chinese markets); being able to enter into art investment as a means to diversify assets with little art knowledge or up front capital; and, not having to directly finance the care and storage of the works.

Many art collectors, however, would frame these points as disadvantages. For example, shouldn’t investing in an artwork also yield some joy in being able to admire and display the work at your own discretion? With an art investment fund, ownership is fractional (appraisers beware!), meaning you likely have no say in the works purchased by the fund. While investors can select from funds with different mandates (more on this below), they ultimately have little personal connection to the art itself. All this is compounded by market volatility, instability, and the potential for significant investment losses.

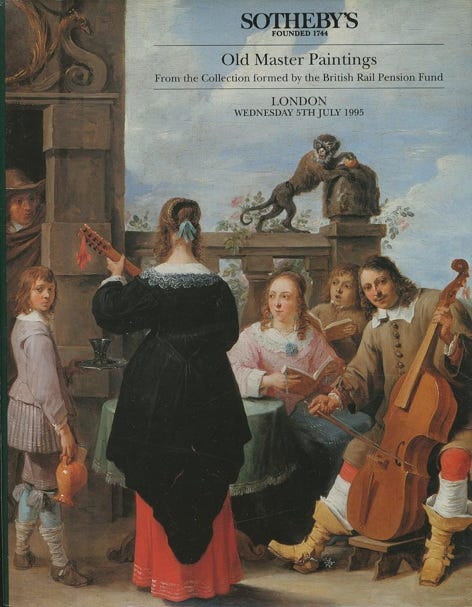

The first notable art fund was the British Rail Pension Fund in 1974 when they invested £40 million in 2,500 works of art during a six-year period. It was reportedly able to deliver an aggregate return of 11.3% per year compounded from 1974 to 1999. Interestingly, while the works purchased by the Fund were largely kept a secret, they were often shown in museums as anonymous loans. A 1978 Washington Post article speculated that the assets included “a Renoir portrait of Cezanne dated 1880; a 1779 bust of Benjamin Franklin by Houdon, similar to the one in New York's Metropolitan Museum; a sketch for a ceiling fresco by Tiepolo; some unspecified Canalettos and a whole range of other items from Louis XVI ormolu candelabra to a German silver gilt coconut cup and cover.” A real mixed bag—not exactly a collection built around a cohesive vision or passion.

The collection was sold across the next two decades, with the final lots sold at a Sotheby’s sale in the late 90s. Reflecting on the fund in a 1996 issue of Museum Management and Curatorship, despite claims that “the Pension Fund would have done appreciably better if it had placed its £40m in a Post Office Savings Account instead […] the portfolio assembled by the British Rail Pension Fund could rarely be faulted and amongst its most successful investments were the Impressionist paintings purchased for £3.4m and auctioned at almost the top of the market, in April 1989, for £33.5m, thereby yielding a real annual rate of return of 2.9%, while the fine group of Old Master paintings sold in July 1996 resulted in a loss in real terms of 0.4% per annum.”1

It is generally agreed that, in the pantheon of all investments one could make, art funds do not typically achieve the strongest returns. There is a wonderful—and heavily footnoted, if you’re into that kind of thing (I am)—essay in a 2018 issue of the Yale Law Journal that combs through the many attempts at maintaining art funds over the last fifty years. The typical trajectory of these funds, the author notes, has been one of “dissolving due to internal scandals, failing to raise sufficient funds, or liquidating their holdings with losses.”

However—and here we return to Art Market Minute’s question of “are art investment funds evolving?”—since the mid-2010s it appears that many art investment funds have either changed their tack or, for in the case of newer funds, have been founded on a different set of principles and motivations. The recent growth and increased attention toward art funds have been driven by the recovery of the art market and rising art prices, diversification benefits in an unstable global economy, and inflation-hedging properties (apparently no longer the domain of just gold and real estate).

Take for example, The Fine Art Group, previously the The Fine Art Fund founded in 2001. It focuses on comprehensive art services, investments in specific markets, and accountability to investors. As of 2016 the firm managed more than $350 million of the $557 million total amount of assets under management in the U.S. and Europe. However, participation is limited—only 30 to 40 investors are accepted into its funds, with minimum investments ranging from $500,000 to $1 million. Hardly an entry point for the novice collector.

This model contrasts sharply with Masterworks, founded in 2017, where the minimum investment is a mere $20. Masterworks operates by purchasing artworks—about one per week—and then registering them with the Securities and Exchange Commission so investors can trade shares in them. It’s a more flexible and accessible model, but its lower exclusivity means returns are spread thinly across a larger pool of investors.

And then there’s Sweden’s Arte Collectum, which closed its first fund in 2020. aPremised on the idea that “ethical investments deliver more attractive returns,” it follows a private equity model with a six-year investment term. Unlike other funds, Arte Collectum invests in work by historically marginalized or unrepresented artists and has a mandate to loan works to public collections—allowing the public to engage with the art while also amplifying its value and market visibility. A thoughtful strategy for socially conscious investors.

In Canada, art investment funds are relatively rare compared to the U.S. and Europe, largely due to regulatory and tax constraints. While Canada has a thriving art market, there are fewer structured art funds, and most high-net-worth investors looking to include art in their portfolios do so through private acquisitions, gallery relationships, or auction houses rather than formalized funds.

One major challenge to the development of art funds in Canada is taxation. The Canada Revenue Agency treats art differently than other investments, often classifying it as personal-use property, which can limit capital gains exemptions and create complexities in valuation and taxation.

However, Canadian investors are not restricted from participating in international art funds. Investing in funds such as Arte Collectum, The Fine Art Group, or Masterworks offers diversification opportunities and access to a broader, more established art market. The advantage is exposure to global art appreciation trends and the expertise of seasoned fund managers. The disadvantage, however, includes currency risks, potential foreign taxation, and limited control over investment decisions. Additionally, Canadian securities laws may require certain disclosures or approvals for investing in foreign funds, which could add complexity to participation.

Ultimately, while Canada has yet to fully embrace art investment funds as the U.S. and Europe have, the growing global interest in art as an asset class may shape future developments. However, art funds are not without risks, and they may not be the most reliable or rewarding investment. The true value of collecting art often lies beyond financial returns—it is in the personal connection, the joy of living with a work, and the appreciation of its cultural and historical significance. For now, Canadian collectors and investors seeking financial exposure to art must navigate the international market or explore alternative investment structures, but they should do so with a clear understanding that art’s worth cannot always be measured in dollars alone.

Peter Cannon-Brookes, “Art Investment and the British Rail Pension Fund" Museum Management and Curatorship (1996) 406-7.

See also in this Substack:

Alice Xiang, “Unlocking the Potential of Art Investment Vehicles” The Yale Law Journal 127.6 (April 2018): 1698-1741