The Price Gap for Women in Art.

Thoughts on the newest record for a living female artist at auction and if a Canadian might be next.

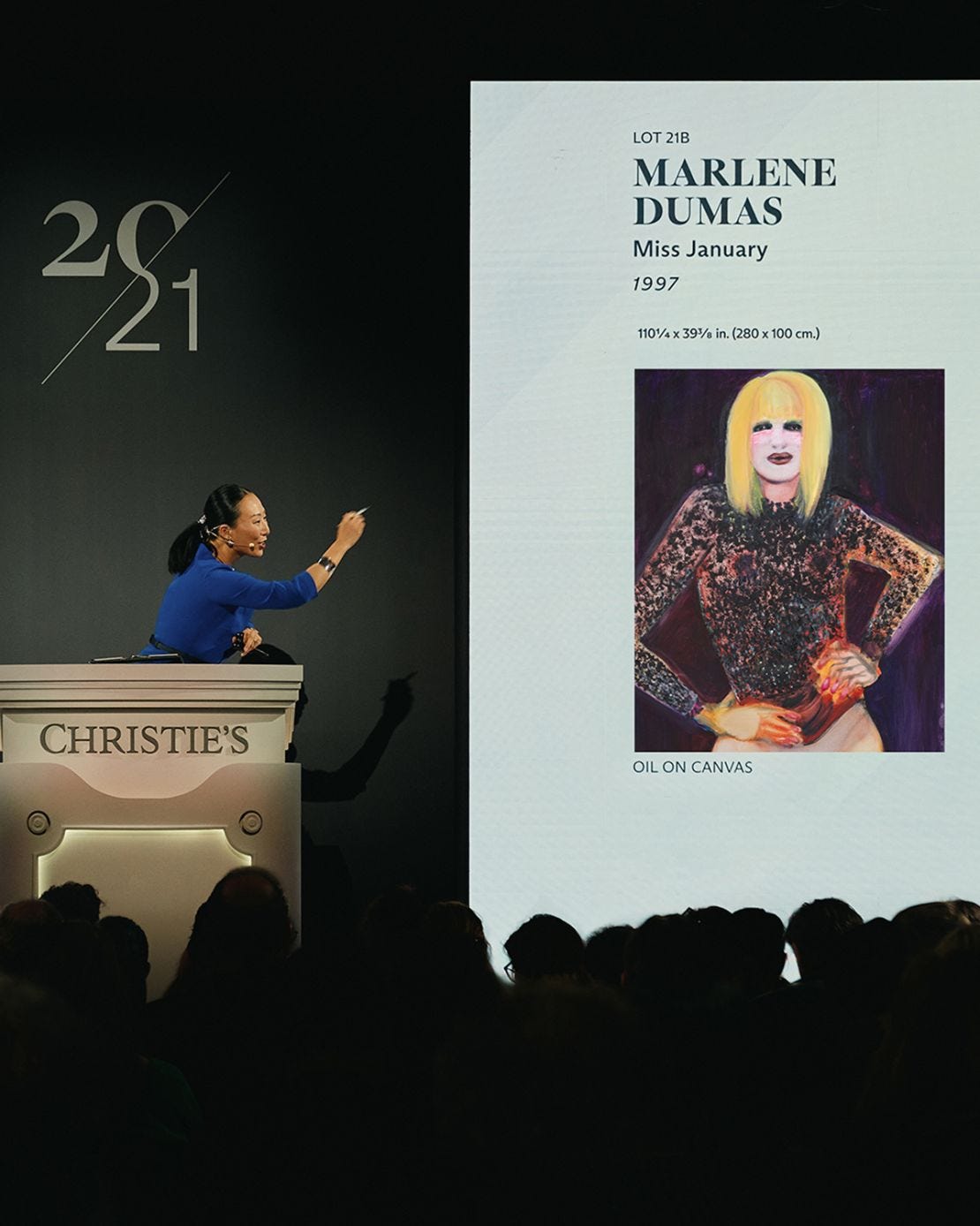

You must have heard by now: a new record was set by a woman artist at auction. South African painter Marlene Dumas has set the new record for a living female artist with the $13.6 million sale of her 1997 painting, Miss January, at Christie’s 21st Century Evening Sale in New York on May 14, 2025. This surpasses the previous record held by Jenny Saville’s Propped, which sold for $12.4 million in 2018.

Miss January is a striking nearly-10-foot-tall portrait depicting a beauty queen standing nude from the waist down, wearing only a single pink sock. The painting, like much of her portraiture, challenges traditional representations of the female body and is considered a significant work in feminist figurative painting of the 1990s.

The painting was consigned by Miami collectors Don and Mera Rubell, who sold it to support their mission of championing emerging artists. The winning bid was placed by Christie’s deputy chairman Sara Friedlander on behalf of an undisclosed guarantor bidder. A guarantor is a buyer who agrees in advance to purchase the work if no higher bids are received.

It was a good week for women artists. The same sale also saw a new record for Simone Leigh. Her bronze sculpture Sentinel IV sold for $5.74 million, surpassing her previous auction record of $3.08 million.

These headline-making sales underscore the increasing attention by collectors and the broader market, directed toward women artists on the global stage. But they also raise a question closer to home: how are Canadian women faring in comparison?

There is, of course, Emily Carr, whose works achieved prices surpassing the C$3 million mark. This record was set on November 28, 2013, when her painting The Crazy Stair sold at Heffel Fine Art Auction House in Toronto. It not only marked the highest price paid for a work by Carr, but also set a record for the most expensive painting by a Canadian female artist at auction. At the time, it was the fourth most valuable piece ever sold in Canadian art auction history. Two other works by Emily Carr sold in 2021 for comparable: Cordova Drift for C$3.36 million in December 2021, and Tossed by the Wind for C$3.12 million in June 2021.

No living Canadian female artist has come remotely close to such figures. That’s not unusual in any national market, where artists often sell for more posthumously. This occurs for several reasons: it’s usually after death when the most scholarship occurs, and when their corpus is finalized both in legacy and volume. Take, for example, Georgia O’Keeffe who holds the record for most expensive painting of all time by a female artist. Jimson Weed / White Flower no. 1, which was sold by Sotheby’s in 2014 and went for $44.4 million nearly twenty years after her death.

In Canada, the highest auction record for a living woman artist belongs to Rita Letendre, a trailblazing Quebec-born painter of Indigenous heritage. Her 1961 work Reflet d’Eden sold for C$451,250 in 2022, while her Terme de la nuit fetched C$289,250 the year prior. These are remarkable prices in the Canadian context, though modest on the global stage.

Compare this with the highest price achieved by a living Canadian male artist. The record is held by Jeff Wall, whose photograph Dead Troops Talk (A Vision After an Ambush of a Red Army patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986) sold for nearly $3.7 million USD in 2012. That’s close to eight times more than Letendre’s record. We might even look more broadly. Heffel has a list of their top 100 Canadian artists on their site based specifically on their own past sales. It provides a good sampling of a larger picture. Lawren S. Harris, Jean Paul Riopelle, and Emily Carr take the top spots. It’s not until the 28th spot that we see another woman: Sybil Andrews, followed closely by Helen McNicholl, Maud Lewis and then Rita Letendre in 37th place. It’s also crucial to point out that save for Letendre, all the women in the top 50 of the list are white.

Letendre’s rise, decades after her involvement with the Automatistes and Plasticiens, speaks to a slow but growing recognition of her contribution to abstract art. But it also underscores a troubling gap. If $450,000 is the highest price a living Canadian woman can command at auction, and yet she comes in 37th in total sales at one of Canada’s premier auction houses for Canadian art, we should be asking: what are the forces shaping these ceilings for women artists on the Canadian market?

There are a few possibilities around why more living—and historic—Canadian women artists haven’t broken into the upper echelons of the art market. It may be that auction houses and collectors remain risk-averse, often investing in already-proven (read: male and/or international) names. If art is an investment, playing it safe by playing it male is a prudent move. Albeit one that reinforces the dominance of male artists in both private and institutional collections. It may also be that the secondary market for contemporary Canadian art is thin, especially for women. Many living artists now achieve greater success through dealer representation at the national and international level. And, lastly, Canadian institutions, though robust in curatorial support, haven’t always translated that support into collector enthusiasm or international exposure.

Even at Art Toronto, Canada’s biggest contemporary art fair, the top sale for a living Canadian female artist came in at just C$26,500 for a painting by the legendary Françoise Sullivan in 2022—a sum would likely be overlooked entirely at fairs like Frieze or Art Basel.

One name that disrupts this narrative is Kapwani Kiwanga. Though her auction results remain relatively quiet, her career is anything but. Her name frequently appears on lists of the most influential contemporary artists. In fact, on this Artfacts ranking of top artists that in their words “measures the influence and success of artists within the context of the entire market,” Kiwanga is ranked 100 in the world. One below Anish Kapour and a few up from Richard Prince (whom the site mistakenly lists as both American and Canadian, likely confusing him with the UBC professor of the same name) and Marlene Dumas. She is the only Canadian on the list.

That Kiwanga is on the list makes sense. She is represented by the prestigious Goodman Gallery, Galerie Poggi, and Galerie Tanja Wagner. Her inclusion in major biennials, most notably the Canadian representative at the 2024 Venice Biennale, institutional shows, and critical discourse suggests a market potential that hasn't yet translated into auction results. Private sale data is, unfortunately, not publicly available, so it is almost impossible to speak to what collectors and institutions might be paying for her works (there are not enough subscribers to have me call up Goodman pretending to be the private secretary of a wealthy collector… yet.)

This divergence between critical acclaim and market value isn’t unique to Kiwanga, but it’s telling. In the Canadian ecosystem, where public funding, academic validation, and collector activity often operate in silos, such gaps are particularly wide.

To see a Canadian woman artist cross the million-dollar threshold while still living, it won’t come from auctions alone. The private market will need to build that value long before a work hits the block. And, institutions will need to do more than celebrate women artists posthumously. Marlene Dumas and Simone Leigh didn’t achieve record sales because they were exceptional alone. They did so not through exceptionality alone, but through sustained support from public funding bodies, national and international institutional exposure, thoughtful curatorial investment, consistent gallery representation, critical writing, and collector interest—each playing a role in building the visibility and longevity that ultimately translate into market value.

Canada has no shortage of remarkable women artists. While Canada’s art market reflects the global patterns of disparity between male and female artists, and between the living and the late, with sustained support and belief, there’s every reason to think that more Canadian women artists will rise to the top of the market.